The Federal Reserve vs Donald Trump: Act I

Author

The beginning of November was marked not only by the outcome of the US presidential elections. On 7 November, the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) announced a 0.25 point cut in the Federal Reserve’s target rate. This was the second rate cut, following the 0.5 point cut announced on 18 September. The impact of monetary policy hinges on its transmission to market rates, and in particular long-term rates, which are also influenced by the future outlook of public debt and deficits. Expectations of a deterioration in the budget balance following the Republican candidate’s victory interact with the decision of the Federal Reserve. Moreover, Donald Trump was highly critical of the Federal Reserve’s rate hike decisions during his first term in office. New tensions could arise as early as January with Jerome Powel, if the President puts pressure on the pace of rate cuts.

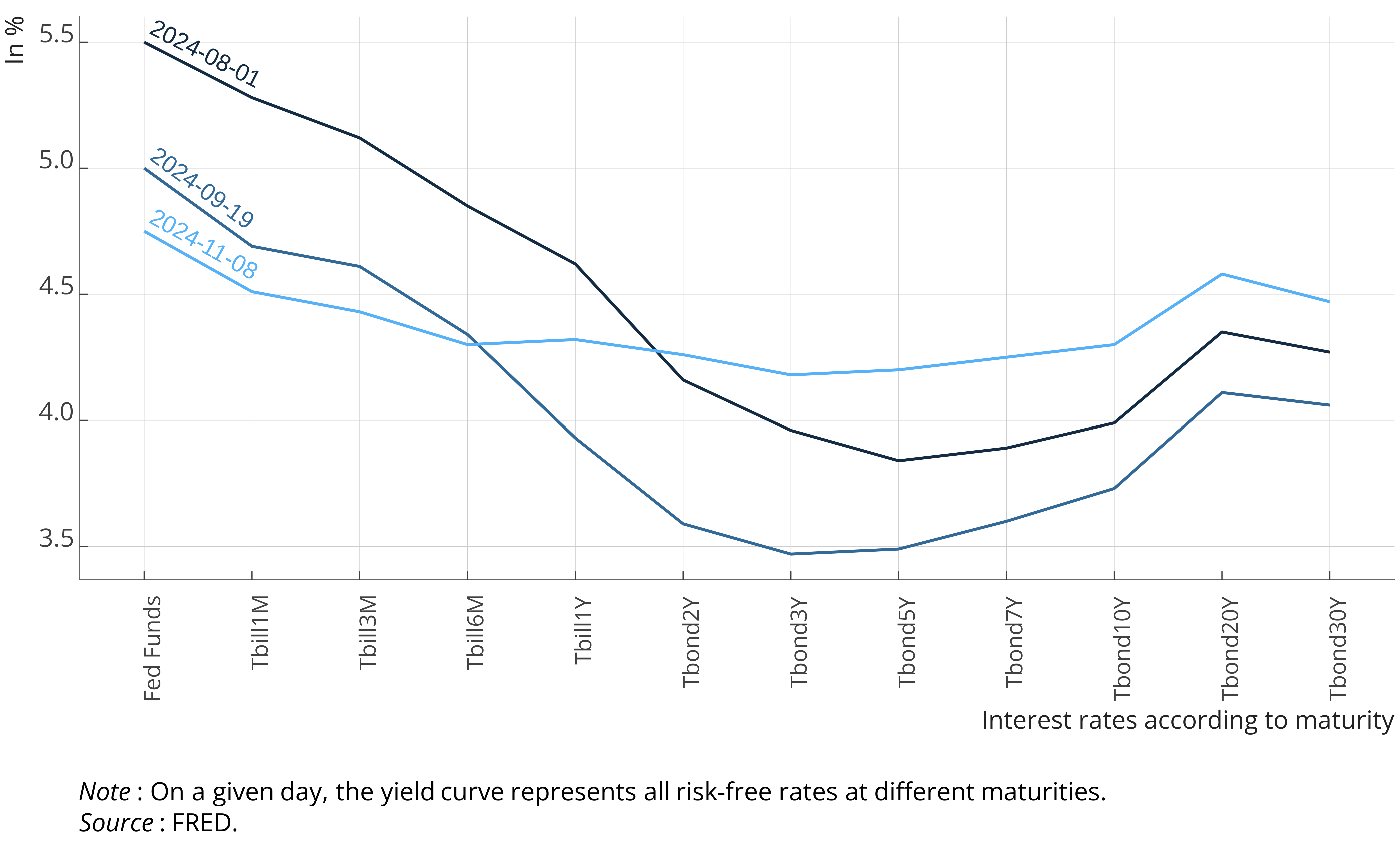

The central bank’s objective is to influence financing conditions in order to achieve its inflation and growth objectives. With US inflation falling, the Federal Reserve considers it can now ease monetary policy to support growth and full employment. This is why, in September, it decided to cut rates for the first time since 2020. This cut has been passed-through Treasury yields at all maturities (graphic 1). The effect of November’s cut was more mixed. While the reduction in the Federal Reserve’s target rate (Fed Funds rate) has been passed on to very short-term Treasuries rates, the yield curve shows that longer-term rates have not fallen and are even higher than those seen at the beginning of August.1 Yet Donald Trump’s victory was widely welcomed by the stock markets, which rose sharply in the days following the announcement of the results. So how can we explain this more mixed trend in interest rates?

1 Securities issued by the US Treasury are Treasury-Bills for maturities of less than two years and Treasury-Bonds for maturities from 2 to 30 years.

One reason could be that the markets had already priced future interest rate cuts after the September decision. According to the expectations theory of the term structure of interest rates, long-term rates reflect expectations of future short-term interest rates. Consequently, a central bank rate cut will have an effect on long-term rates if the markets expect it to be followed by additional cuts. Not only was September’s announcement larger, it also signalled a change of direction by the Federal Reserve, with the beginning of a new easing cycle. This decision had therefore a greater informational content than the November’s cut, which would have contributed to the fall observed between the meeting of 31 July and that of 18 September. However, this explanation is not consistent with the rise in rates across all maturities over 2 years between the beginning of August and the beginning of November.

Another possibility is that Donald Trump’s victory has altered expectations about the path of public debt and inflation. During the campaign, the former President announced a series of tax cuts that could lead to a widening of the deficit and a rise in the debt estimated at almost 10 percentage points by 2035, according to estimates of Penn Wharton Model. This expected increase in the supply of debt securities could therefore drive interest rates higher. Trump’s announcements also include higher tariffs and the mass deportation of migrants. Both of these measures are likely to increase inflation, since the rise in customs duties will increase the cost of imported goods, while the expulsion of immigrant workers could lead to tensions on the labour market and therefore a rise in labour costs, which will also be passed on to prices.2 At constant real yields, an increase in expected inflation pushes up nominal yields. The yield of inflation-linked bonds, provides information on the breakdown of the nominal rate described by the yield curve between the real yield and inflation expectations.3 Since September, real rates and expected inflation (known as BEIR for Break-even inflation rate) have been on the rise again (graphic 2). The 0.7 point rise in the nominal 5-year yield between 19 September and 8 November is explained by a 0.3 point rise in the real yield and a 0.4 point rise in expected inflation. On the 10-year yield, the contribution of expected inflation (0.2) is smaller than that of the real yield (0.4).

2 See this analysis from the Petersen Institute for International Economics.

3 Treasury inflation protected securities (TIPS) are securities with coupons and principal adjusted to take account of inflation. The price of these securities is therefore used to determine the real yield (adjusted for inflation). The difference between the nominal yield on a standard bond and an index-linked bond of the same maturity provides a proxy for inflation expectations over the time horizon.

The impact of monetary policy depends on the transmission of central bank decisions to financial conditions as a whole, and to long-term interest rates in particular, since it is these variables that influence the consumption and investment behaviour of households and firms. Donald Trump’s victory and the consequences of his economic programme could therefore lessen the impact of the monetary easing implemented by the Federal Reserve.

Beyond these short-term effects, Donald Trump’s re-election could lead to tensions between the President and the Federal Reserve. During his first term in office, Donald Trump often criticised Jerome Powell’s action when he raised interest rates between late 2016 and 2018. Donald Trump’s victory is seen as a potential threat to the central bank’s independence. Indeed, according to the New York Times, he declared during the campaign that ‘the President should have a say on interest rates’. While it will be difficult for the President to force Jerome Powell to resign,4 pressure could intensify for the Federal Reserve to cut rates faster. What impact would this have on long-term interest rates? It will be difficult for Donald Trump to coerce the markets. The current rise in long-term rates is not the result of monetary policy, but rather of the measures promised by Trump, which should result in higher inflation and more public debt. Nevertheless, (Tillmann, 2020) and (Bianchi et al., 2023) have shown that the many statements made against Jerome Powel and the Federal Reserve during its first mandate have had an impact on long-term rates, with the markets anticipating a fall - or a smaller rise - in future monetary policy rates. We will therefore probably have to wait until January to see whether there will be an Act II with a challenge of the Federal Reserve’s independence, which could result in lower rates.

4 Jerome Powell, whose term of office ends in May 2026, has already stated that he will not resign.